Translate this page into:

Acquired choroidal osteoma

*Corresponding author: Arun D. Singh, Department of Ophthalmic Oncology, Cleveland Clinic Cole Eye Institute, 9500 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio, 44195, United States. singha@ccf.org

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Purgert RJ, Echegaray JJ, Lauer S, Singh AD. Acquired choroidal osteoma . Lat Am J Ophthalmol 2019;2(2):1-3.

Abstract

Choroidal osteoma is a choristomatous lesion postulated to be congenital in nature. Described herein is the case of a 16-year- old female presenting with a peripapillary lesion diagnosed as choroidal osteoma on multimodal imaging. Routine fundus photography 18 months before presentation demonstrated a normal retina and choroid without evidence of the lesion. Overall, this report provides evidence that choroidal osteoma may be acquired and not always congenital in origin.

Keywords

Indocyanine green angiography

Ocular imaging

Oncology

Retina

tumor

INTRODUCTION

Choroidal osteoma is of comprised osseous tissue in the choroid.[1,2] Histologic analysis of choroidal osteoma, also known as osseous choroidal choristoma, reveals bony trabeculae comprised of numerous osteocytes and occasional osteoclasts, with marrow spaces containing young mesenchymal cells.[1,2] In addition, there is obliteration of the choriocapillaris in most areas, depigmentation or irregular pigment clumping in the overlying pigment epithelium, and focal degeneration of retinal photoreceptor outer segments.

Choroidal osteoma is believed to be a developmental tumor arising from congenital rests of primitive mesoderm.[1] Factors such as ocular inflammation, systemic metabolic abnormalities, or hormonal changes have been implicated in etiopathogenesis; however, in most reports, suggestion of an acquired origin of choroidal osteoma remains speculative since documentation of a normal retina and choroid before observation of the osteoma is lacking.[3-6]

Herein, we present a case of an acquired choroidal osteoma developing in normal choroid within an 18-month interval. This report is compliant with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

CASE REPORT

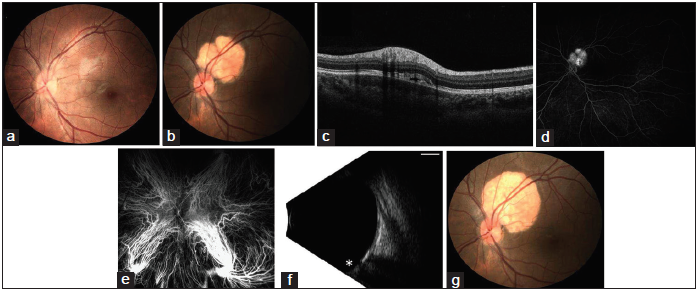

A 16-year-old female presented for evaluation of a left eye peripapillary lesion that had been noted 3 weeks prior by her local optometrist, who had provided routine eye care for the past 2½ years. The lesion had apparently developed since her last visit 18 months prior since routine color fundus photography obtained at that time revealed no evidence of the lesion [Figure 1a]. On presentation, the visual acuity was 20/20 with normal anterior segment findings bilaterally. The right eye examination was unremarkable. In the left eye, a 3.5 × 3.5 × 1.0 mm orange, circumscribed mass located superotemporal to the optic disc was observed. There was no associated hemorrhage, drusen, or orange pigment [Figure 1b]. Optical coherence tomography through the lesion revealed retinal inner and outer segment disruption and trace subretinal fluid associated with underlying focal choroidal thickening [Figure 1c]. Fluorescein angiography revealed staining of the lesion without leakage [Figure 1d]. Indocyanine green angiography (ICG) showed early hypocyanescence [Figure 1e] followed by late hypercyanescence. Ultrasound B-scan showed a hyperechoic choroidal lesion 1 mm in height with marked shadowing effect [Figure 1f]. The patient’s review of systems and medical history were unremarkable. These findings were consistent with a choroidal osteoma. We recommended observation with routine follow-up. The lesion was observed to grow in basal dimensions (4.0 × 4.0 mm) [Figure 1g] with stable height at 5 months. As the patient was asymptomatic with an otherwise normal examination, observation was again recommended.

- (a) A 16-year-old female presenting with a left eye peripapillary lesion. (a) Normal fundus photograph of the left eye 18 months before presentation. (b) Fundus photograph of the left eye on presentation demonstrating a circumscribed lesion superotemporal to the optic disc without hemorrhage, drusen, or orange pigment. (c) Optical coherence tomography demonstrates focal thickening and hyporeflectivity of the choroid, associated with trace subretinal fluid and retinal inner segment/outer segment disruption. (d) Fluorescein angiography at 9 min reveals staining of the lesion without leakage. (e) Indocyanine green angiography at 0.5 min reveals early hypocyanescence in the area of the lesion. (f) B-scan ultrasonography reveals the optic nerve (*) with the lesion that is 3.5 mm × 3.5 mm × 1 mm in height with high reflectivity causing marked shadowing of the orbit. Scale bar 5 mm, gain 57 dB, frequency 10 MHz. (g) The lesion demonstrated interval growth (in basal dimensions) at 5-month follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Multimodal imaging allowed diagnosis of a choroidal osteoma, excluding other entities, such as choroidal hemangioma, inflammatory granuloma, or scleritis.[7] ICG specifically was helpful in distinguishing these entities, as hemangiomas demonstrate early hypercyanescence and late hypocyanescence due to washout, while choroidal osteomas demonstrate early hypocyanescence, and late hypercyanescence, as observed in our case.[8,9] B-scan ultrasonography indicated the presence of intrinsic calcification further supporting a clinical diagnosis of choroidal osteoma.

We present here a case demonstrating onset of choroidal osteoma with prior imaging of normal choroid, supporting the notion that choroidal osteomas are acquired lesions, in at least some instances. Continued growth over a short period of observation (5 months) further supports an acquired origin. Many reports suggesting an acquired etiology of choroidal osteoma remain in some sense speculative as they lack image proof of a normal choroid before identification of a choroidal osteoma. To the best of our knowledge, there is only one previous report of a 62-year-old male with apparent development of a choroidal osteoma in the area of prior sectoral panretinal photocoagulation for branch retinal vein occlusion, though this report lacked ICG to confirm choroidal osteoma over other entities.[10] The stimulus for the development of the choroidal osteoma in the present case remains open to speculation, but hormonal influences seem most likely in this teenage female in the absence of abnormal calcium and phosphorus metabolism.[4-6]

CONCLUSION

The patient with normal fundus 18 months before presentation was diagnosed with new choroidal osteoma on multimodal imaging. Our report provides evidence that choroidal osteoma may be acquired and not always congenital in origin.

Institute Review Board approval

Case reports are exempt from Institute Review Board approval as long as patient identity is not revealed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, New York) unrestricted grant to the Cole Eye Institute (RPB1508DM), Foundation Fighting Blindness (Columbia, Maryland) grant to the Cole Eye Institute (CCMM08120584CCF), and National Eye Institute/ National Institute of Health (Bethesda, Maryland) P30 Core Grant (IP30EY025585).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Osseous choristoma of the choroid simulating a choroidal melanoma. Association with a positive 32P test. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96:1874-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choroidal osteoma after intraocular inflammation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;96:759-64.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Multiple choroidal osteomas developing in association with recurrent orbital inflammatory pseudotumor. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101:1724-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- New observations concerning choroidal osteomas. Int Ophthalmol. 1979;1:71-84.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choroidal osteoma presenting in pregnancy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:612-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemangioma of the choroid. A clinicopathologic study of 71 cases and a review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol. 1976;20:415-31.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Indocyanine green angiographic findings in choroidal hemangiomas: A study of 75 cases. Ophthalmologica. 2000;214:246-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indocyanine green angiography in choroidal osteoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1997;235:330-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De novo appearance of a choroidal osteoma in an eye with previous branch retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2013;44:77-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]