Translate this page into:

Sebaceous gland carcinoma of ocular region in India: A brief literature review for disease management

*Corresponding author: Ankit Srivastava, Department of Biotechnology, Motilal Nehru National Institute of Technology, Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh, India. anku054@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Srivastava A, Sharan S. Sebaceous gland carcinoma of ocular region in India: A brief literature review for disease management. Lat Am J Ophthalmol 2021;4:4.

Abstract

Sebaceous gland carcinoma (SGC) is slow growing, but the most aggressive and lethal eyelid malignancy. Histologically, SGC can be classified based on cell types, cytoarchitecture, and growth patterns. A previously published article illustrates the molecular genetic framework stating the drivers of sebaceous carcinoma. Today, every effort has been made to treat and eradicate ocular disease, therefore, early diagnosis and appropriate management are required to use a multimodal approach that can reduce the mortality rate in patients with SGC. Treatment with the conventional technique has improved visual and systemic prognosis, however, therapeutic target to treat cancer is a much better option than other modalities. Thus, new insight into the natural and molecular-oriented treatment modalities may lead to the development of new effective strategies, along with the conventional method.

Keywords

Clinicopathological

Eyelid

Natural products

Sebaceous gland carcinoma

Therapeutic target

INTRODUCTION

Ocular oncology is increasing rapidly with new developments and attracting broad, worldwide attention as well. This field covers a diverse spectrum of ocular benign or metastatic tumors, ranging from lymphoma to retinoblastoma to melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), sebaceous gland carcinoma (SGC), and adenoid cystic carcinoma. Most of the ocular malignancies are treatable if detected early on time. However, some malignancies become highly problematic due to their metastatic behavior and cause a potential threat to both sight and life. Among the various ocular malignancies mentioned elsewhere, eyelid tumors are the most commonly known in the Asian-Indian population. Approximately 5% of skin tumor occurs in the eyelid.[1] Among them, basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common eyelid malignancy worldwide 85–90 %[2] followed by SCC 10–12%[3] and SGC 1%.[4] Mostly known, SGC used to be a uniformly fatal disease and has become the topmost malignancy over this past century. It is the most aggressive tumor that is associated with the hair follicle and abundantly present in the skin where more hair is found with a slight predominance in females. High mitotic activity is found in the sebaceous gland but the neoplasm arising from here is uncommon. It mimics various benign and malignant lesions, therefore, shows variability in clinical presentation. At present, in most countries, SGC is the most successfully treated ocular cancer. In other countries except for Asia, the incidence among eyelid malignancies is 1–5.5%.[5] However, in Asian-Indian races, it comprises 25–40% of all eyelid neoplasm. Clinically, it masquerades benign and inflammatory conditions such as chalazion and blepharitis which may result in late diagnosis.[6] It may involve forniceal and bulbar conjunctiva with diffuse thickening of the eyelid. An irregular yellow mass appears on the caruncle in SGC. From this review, we are emphasizing the outline of SGC based on existing literature and also highlighting the treatment and therapeutic option which is one of the most challenging aspects for prognosis and management of the disease.

LITERATURE SURVEY

The literature survey for the present review was based on results searched on PubMed, Medline, and Google Scholar database search using the words eyelid tumors, sebaceous carcinoma, SGC, sebaceous neoplasm, and sebaceous cell carcinoma. Selected literature under this review was published only in the English language. In addition, some relevant references were also gathered and included from the selected articles.

FEATURES AND EPIDEMIOLOGY OF SGC

Sebaceous carcinoma commonly arises from the ocular adnexa and eyelid but may also be found in the periocular area. It is observed that the majority of all skin malignancies around 5–10% occur in the eyelid and among all the eyelid malignancies, BCC is mostly known.[1] In the United States, BCC is mostly acknowledged in about 90%, SGC accounts for 5% followed by SCC 4% and 1% covers the other malignancies.[4] However, due to differences in geographical variation, the incidence of different malignancies would vary. Similarly, SGC shows mystifying variation area to area according to geographic area surveyed and hence appears to have racial preferences. Reports from Florida states the annual incidence of patients having eyelid malignancies was 0.5 per million in older than 20 years.[7] In contrast, reports from China and India reflect higher incidence 31.2–39.0% of patients suffering from eyelid malignancies. The incidence has risen over the last years because of the longer lifetime of individuals (sebaceous carcinoma tends to be a neoplasm that affects older individuals), increased awareness of the disease by pathologist, dermatologist, ophthalmologist, or the fact that the United States contains a more varied population mainly from Asia. Moreover, there has been an increase in sebaceous carcinoma of the periorbital area rather than the orbital tumor.[8]

MAJOR RISK FACTORS OF SGC

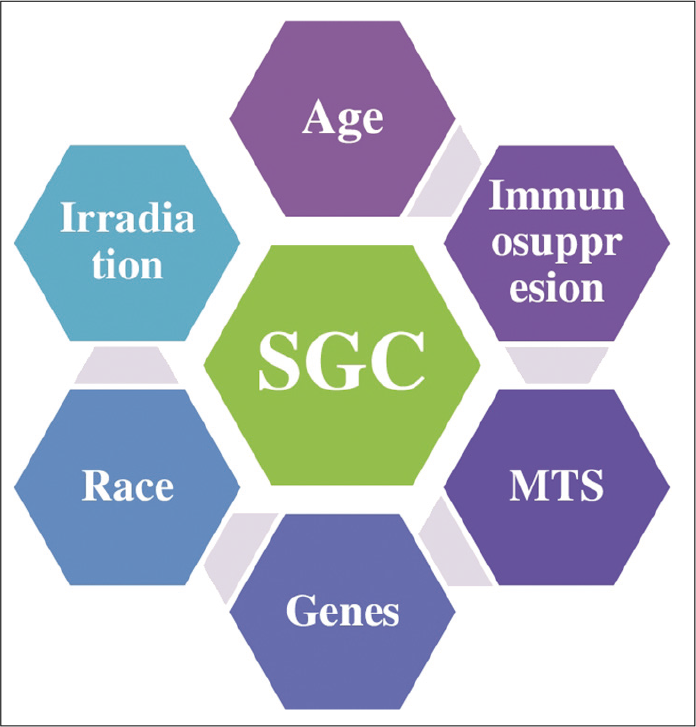

SGC has some major risk factors which include patient’s age, prior exposure to UV, systemic association, and patients infected with HIV and Muir-Torre syndrome [Figure 1].

- Relative risk factors for ocular sebaceous gland carcinoma.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid commonly can masquerade as a benign condition (masquerade syndrome), often resulting in a delay in diagnosis.[9] This, in turn, can increase the chance of local recurrence, metastasis, and death. Finding suggests that SC may sometimes grow outward and become pedunculated with keratinization and also possess a cutaneous horn-like appearance. It occurs most commonly in the eyelid margin from the gland of Zeis.[10,11] Less commonly, SGC may ulcerate and have BCC appearance. The most common clinical manifestation presents as a firm, sessile to round, painless, and subcutaneous nodule in the eyelid.[12] It assumes a yellow color due to the presence of lipid in the mass. Eventually, it causes loss of cilia, a feature present in other tumors too. The second most common manifestation is pseudoinflammatory which present as diffuse unilateral thickening of the eyelid. This presentation is more likely to extend to the epithelium of nearby structures such as the cornea and conjunctiva. The lack of a nodule causes the clinician to suspect an inflammatory condition.[13,14] It is also suggested that SGC must be ruled out in unilateral blepharitis in an older patient that does not respond to standard treatment, and thus, biopsy is indicated. With the development of sebaceous carcinoma in the caruncle, it looks like an irregular, yellow mass in the medial canthal lesion.[15] Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyebrow has the appearance of a deep cutaneous mass that may be difficult to distinguish from the epidermal inclusion sebaceous cyst. Sebaceous carcinoma may also present as diffuse involvement of the eyelids, conjunctiva, cornea, and anterior orbital tissue. Progressive enlargement of the sebaceous carcinoma in the lacrimal gland region may be found in very rare instances.[16,17]

ORIGIN OF OCULAR SEBACEOUS CARCINOMA

Sebaceous carcinoma develops from some specific gland and periorbital area including gland of Zeis, meibomian gland, glands associated with hair follicle, caruncle, conjunctiva, and sebaceous gland with eyebrow which are discussed below: Gland of Zeis gives rise to 10% sebaceous carcinoma. SGC of the eyelid is more profound at the upper eyelid but it may also found at both the upper and lower eyelids simultaneously. The incidence of sebaceous carcinoma arising from the caruncle is very low approximately 5-10%. Number of ophthalmic literatures suggests that sebaceous carcinoma of the eyebrow is rarely observed.

DIFFERENT CLINICAL DIAGNOSTIC OF SGC

SGC is the most aggressive tumor of the eyelid, thus its accurate diagnosis and treatment are important. Its diagnosis is difficult because SGC resembles several neoplastic lesions and inflammatory conditions such as chalazion or chronic blepharoconjunctivitis and blepharitis leading to the term “masquerading syndrome.”[18,19] The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) recommendation defined tumor node metastasis to access the tumor staging. AJCC classification on the recent staging of SGC based on the eighth edition is given in Table 1.[20]

| Primary tumor (T) | Definition |

|---|---|

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be evaluated |

| T0 | No primary tumor |

| Tis | Refers to carcinoma in situ |

| T1 | Size of tumor ≤10 mm in diameter |

| T1a | No invasion of tarsal plate or eyelid margin |

| T1b | Invasion of tumor in tarsal plate or eyelid margin |

| T1c | Involvement of tumor in full thickness of eyelid |

| T2 | Tumor size >10 mm but ≤20 mm in diameter |

| T2a | No invasion of tarsal plate or eyelid margin |

| T2b | Invasion of tumor in tarsal plate or eyelid margin |

| T2c | Involvement of tumor in full thickness of eyelid |

| T3 | Tumor size >20 mm but ≤30 mm in diameter |

| T3a | No invasion of tarsal plate or eyelid margin |

| T3b | Invasion of tumor in tarsal plate or eyelid margin |

| T3c | Involvement of tumor in full thickness of eyelid |

| T4 | Tumor invading the orbital, facial, and ocular structure |

| T4a | Tumor invading the intraorbital and ocular structure |

| T4b | Tumor invading the lacrimal sac, nasolacrimal duct, brain and erosion of bony orbital walls, or those with paranasal sinus |

| Lymph node (N) | |

| NX | Regional lymph node cannot be evaluated |

| N0 | Refers to no regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis <3 cm in diameter |

| N1a | Metastasis based on clinical evaluation or imaging |

| N1b | Metastasis proved by histopathology |

| N2 | Regional lymph node metastasis >3 cm in diameter with involvement of bilateral and contralateral lymph node |

| N2a | Metastasis based on clinical evaluation or imaging |

| N2b | Metastasis proved by histopathology |

| Distant metastasis (M) | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis evaluated |

| M1 | Metastasis to other body parts |

AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer, TNM: Tumor node metastasis

METHODS OF SPREAD

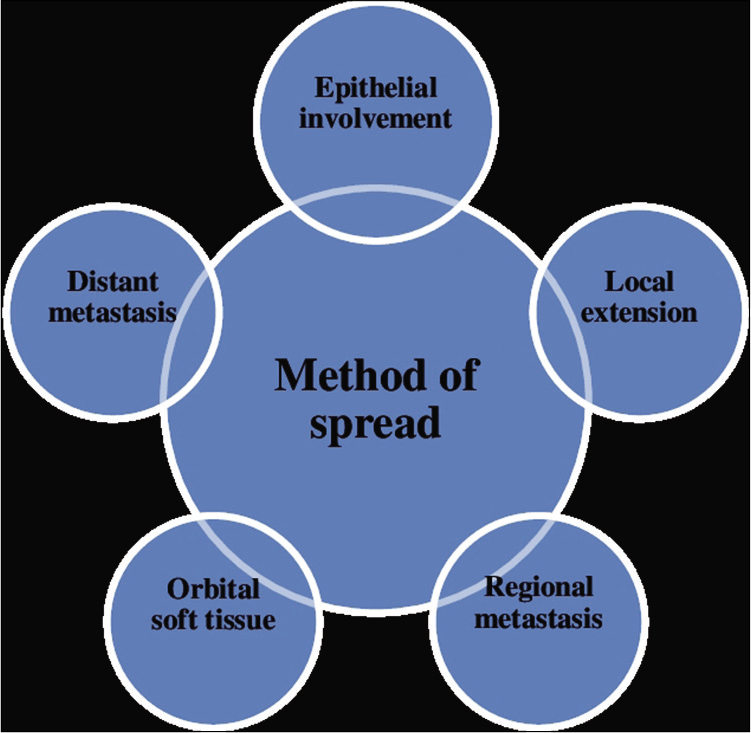

Metastasis of the original tumor cells to sites distant from the original sites may take the majority of the death associated with cancer. This quite complicated process is also observed in sebaceous carcinoma which is one of the most clinically challenging aspects. The different methods of spread highlighted in Figure 2.

- Sebaceous carcinoma has ability to migrate beyond its original location. Here are some of the methods given through which sebaceous carcinoma is shown to exhibit metastasis.

PATHOLOGICAL AND MORPHOLOGICAL SPECTRUM OF SEBACEOUS CARCINOMA

SGC is often misdiagnosed with other periocular and eyelid malignancies during the histopathological diagnosis[21] which makes it challenging in the present scenario. Therefore, sebaceous carcinoma is misdiagnosed with BCC, SCC, or other malignancies. Even when the diagnosis is correct, there is often a misinterpretation of the margins. About 25% of cases of Mohs microsurgery technique fall under the category of non-reliable.[8] This type of misinterpretation often leads to inappropriate treatment in most cases.

GROSS PATHOLOGY

No specific gross characteristics regarding SGC have been reported. Neoplasms may have yellow color due to lipid deposition. Specimens of the tumor eyelid biopsy may show it arising in the tarsal plate.

MICROSCOPIC PATHOLOGY

Apart from several methods applied to classify the neoplasm, some more histopathological patterns are recognized such as lobular, comedocarcinoma, papillary, and mixed.[22,23]A well-known characteristic feature of SGC is its ability to exhibit intraepithelial spread into the conjunctival, eyelid, and corneal epithelium;[24] this occurs in 44–80% of the cases.[25] Regardless of the pattern of growth discussed elsewhere, SGC has distinct cytologic features such as individual cells having finely vacuolated, frothy cytoplasm.[12] Lipid deposition in the tumor may induce a foreign body granulomatous reaction that may resemble a chalazion clinically. Pleomorphism and high nuclear mitotic rate are frequent features. A useful stain for SGC is oil-red O stain which highlights the lipid deposition in the glandular cells. Hence, for the final diagnosis, the entire histopathologic features must be taken accurately. Pathology of the diseases can be made only for looking into the morphological characteristics.

It was also concluded that the morphology of SGC can be classified by the degree of differentiation of cells ultimately differentiated into well defined, moderately and poorly defined. Various clinicopathological factors are reported to indicate a poor prognosis in SGC and include lymphovascular and orbital invasion, involvement of both upper and lower eyelids, poor differentiation, multicentric origin, long duration of symptoms, large tumor size, an infiltrative pattern, and pagetoid invasion of epithelia of the skin or conjunctiva.[23] According to tumor, invasiveness SGC may be minimally infiltrative, moderately infiltrative, and highly infiltrative groups. Tumors originating from the glands of Zeis have a better prognosis. Furthermore, origin from the upper lids is associated with an adverse prognosis compared to origin from lower lids.[26]

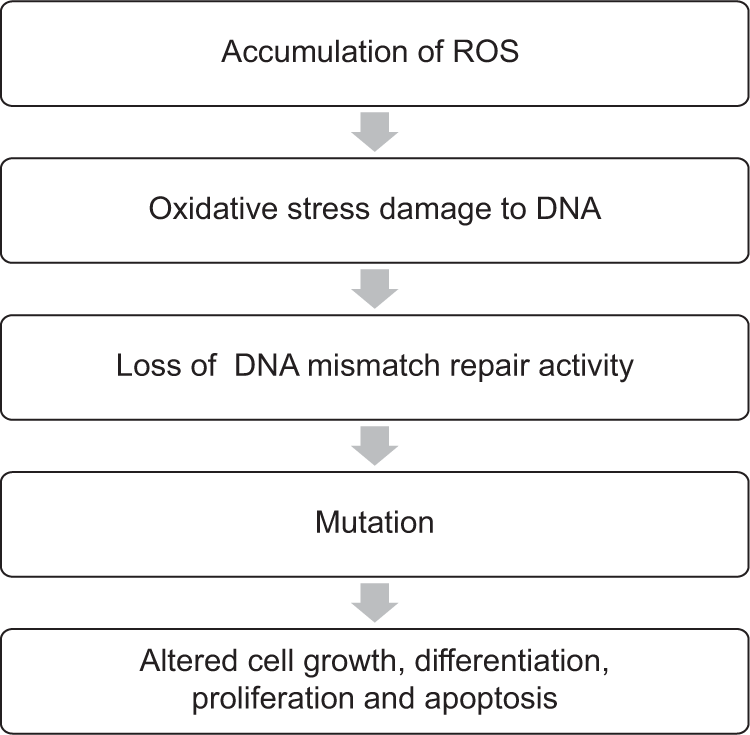

IMPORTANT MOLECULAR ALTERATION IN SGC

Several studies have investigated the genetic alteration driving the sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid. Sebaceous carcinoma is considered as a marker for the Muir-Torre syndrome, an autosomal dominant condition often associated with germline mutation of mismatch repair (MMR) genes MLH1, PMS2, MSH6, and MSH2.[27,28] MMR-deficient cancers have high risk of mutation, caused mostly by UV radiation or oxidative stress results accumulation of reactive oxygen species [Figure 3]. Deficient expression and lack of MMR genes often occur in coordination with loss of other DNA repair genes in cancer. Moreover, carcinoma defective in these genes shows replication error generating a pattern known as microsatellite instability often develop internal malignancies such as endometrial, gastric, genitourinary tract, and colorectal cancer.[29] In addition to the above, it is well known that p53 helps in maintaining cellular integrity and differentiation, however, alteration in the p53 genes has been associated with poor prognosis and plays a major role in carcinogenesis. In a study, approx. 67% of SGC tumors had missense and non-sense mutation in p53 genes and showed immunoreactivity in 50–100% of SGC cases which can indicate alteration of p53 signaling.[30] Moreover, under normal circumstances, expression of Wnt and Sonic-Hedgehog (Shh) was required during stem cell renewal and embryogenesis. Whereas multipotent stem cells required increased expression of Wnt, Shh, and LEF-1 for differentiation into the hair follicle progenitor and sebocyte progenitor, finally developed into the sebaceous gland. The previous studies also revealed the defective β-catenin binding site in the Lef-1[31] leads to accumulation of β-catenin in the cytoplasm and shows overexpression in eyelid developed sebaceous skin tumor and also resulting in upregulation of Indian hedgehog protein expression promotes proliferation of sebaceous precursor cells.[32]

- General hypothesis for oxidative damage to DNA repair activity and tumorigenesis.

THERAPEUTIC TARGET AND TREATMENT FOR SGC

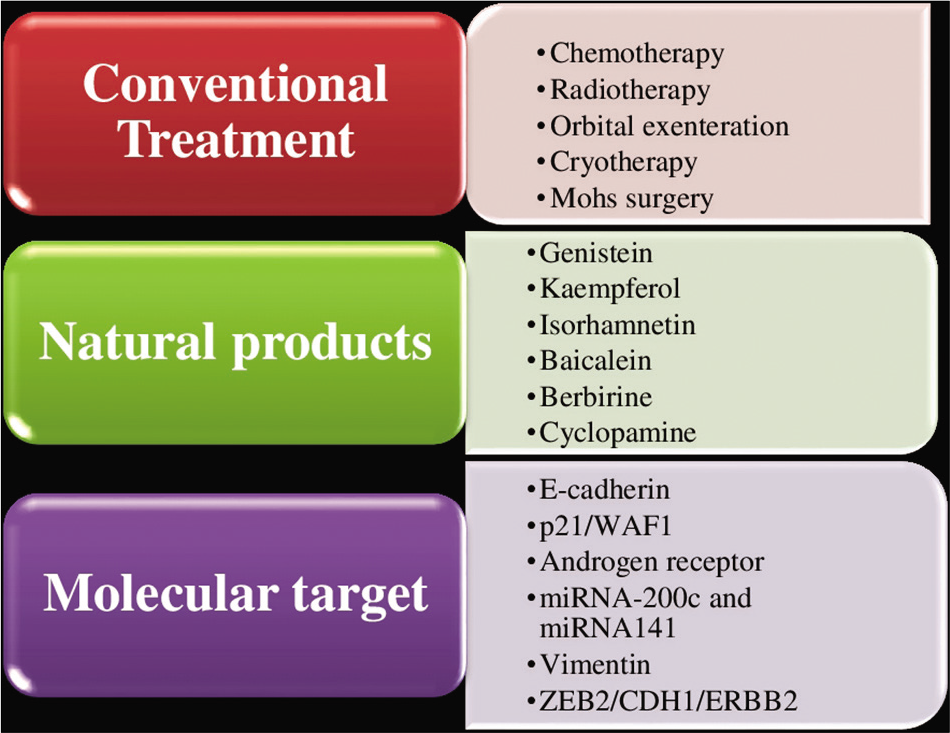

It is well understood that clinical diagnosis of SGC is challenging due to masquerading nature, inappropriate management, delayed detection, and differentiation from other eyelid cancer contribute to poor outcomes. Conventional treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and exenteration [Figure 4] are the methods that are used to manage the SGC patients. Recent multimodal therapy is also helpful in improved management for SGC including a combination of high-dose chemotherapy plus surgery, radiotherapy, and neoadjuvant chemotherapy. However, conventional therapies sometimes are life threatening, therefore, natural products have been considered for their anticancer activity.[33] Indigenous component present in the natural products such as flavonoids, alkaloids, and taxanes has been used to develop chemotherapeutic drugs to treat and cure various cancers such as leukemia, breast, prostate, and ovary including ocular carcinoma.[34-38] Since, little is known about the molecular target as well, here, we highlighted the molecular target implicated in the pathogenesis of SGC.

- Depicting the different treatment and therapeutic target in sebaceous gland carcinoma.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

In eyelid malignancy, SGC is most common in the Indian population. Therefore, early diagnosis and treatment is a major challenge in the present scenario, since no significant prognostic marker is available. With this study, we hope to elaborate the translational research in ocular oncology, and further study will help to improve the diagnostic and prognostic accuracy.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Treatment options and future prospects for the management of eyelid malignancies: An evidence-based update. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:2088-98.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Periocular basal cell carcinoma in adults 35 years of age and younger. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106:723-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Squamous cell carcinoma of the eyelid and conjunctiva. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2009;49:111-21.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rapidly growing extraocular sebaceous carcinoma occurring during pregnancy: A case report. . 2008;14:8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pathologic classification of meibomian gland carcinomas of eyelids: Clinical and pathologic study of 156 cases. Chin Med J. 1979;92:671-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malignant tumor of eyelid: A population based study of non-basal cell and non-squamous cell malignant neoplasm. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:195-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sebaceous and meibomian carcinomas of the eyelid. Recognition diagnosis and management. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;7:61-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sebaceous carcinoma of lid margin masquerading as cutaneous horn. Arch Ophthalmol. 1973;90:380-1.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sebaceous tumor of the ocular adnexa In: Albert DM, Jakobiec FA, eds. Principle and Practice of Ophthalmology Vol 4. (2nd ed). Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2000. p. :3400-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid with Pagetoid involvement of the bulbar and palpebral conjunctiva. J Cutan Pathol. 1977;4:134-45.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chronic unilateral blepharoconjunctivitis caused by sebaceous carcinoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;86:218-20.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sebaceous carcinoma of the glands of Zeis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;4:11-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Primary sebaceous carcinoma of the lacrimal gland. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:625-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Primary sebaceous carcinoma of lacrimal gland: A previously unreported primary neoplasm. Eye (Lond). 1994;8:592-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ocular surface neoplasia masquerading as chronic blepharoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 1999;18:282-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Eyelid carcinoma. In: Edge SB, Greene FL, Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK, Gershenwald JE, eds. Carcinoma of the Eyelid AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (8th ed). New York: Springer; 2017. p. :779-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid, eyebrow, caruncle and orbit. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1968;72:619-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sebaceous gland tumors In: Spencer WH, ed. Ophthalmic Pathology An Atlas and Textbook Vol 4. (4th ed). Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1996. p. :2278-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sebaceous carcinomas of the ocular adnexa: A clinico-pathologic study of 104 cases, with 5-year follow-up data. Hum Pathol. 1982;13:113-22.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelids: Personal experience with 60 cases. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:2151-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Outcome of patients with periocular sebaceous gland carcinoma with and without conjunctival intraepithelial invasion. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1877-83.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Unusual eyelid tumors with sebaceous differentiation in the Muir-Torre syndrome. Rapid clinical regrowth and frank squamous transformation after biopsy. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:1543-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Is the mismatch repair deficient type of Muir-Torre syndrome confined to mutations in the hMSH2 gene. Hum Genet. 1996;98:747-50.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Microsatellite instability and mismatch repair protein expression in sebaceous tumors, keratocanthoma, and basal cell carcinomas with sebaceous differentiation in Muir-Torre syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:509-10.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The genetics of HNPCC: Application to diagnosis and screening. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;58:208-20.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- P53 staining correlates with tumor type and location in sebaceous neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:129-35.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Expression of delta N lef-1 in mouse epidermis results in differentiation of hair follicles into squamous epidermal cysts and formation of skin tumours. Development. 2002;129:95-109.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Indian hedgehog and beta-catenin signaling: Role in the sebaceous lineage of normal and neoplastic mammalian epidermis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(Suppl 1):11873-80.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010. J Nat Prod. 2012;75:311-35.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anticancer drugs from nature-natural products as a unique source of new microtubule-stabilizing agents. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29:12.

- [Google Scholar]

- The future of complementary and alternative medicine for cancer. Cancer Invest. 2005;23:420-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- New anticancer agents: Recent developments in tumor therapy. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:2999-3005.

- [Google Scholar]

- Natural products as leads to anticancer drugs. Clin Transl Oncol. 2007;9:767-76.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Natural products: A continuing source of novel drug leads. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830:3670-95.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]